Picture the scene. You’re in a hurry, on the move, and need to check a website on your phone. You type in what you think was the URL, but get it slightly wrong. The site you’re after appears to load as normal. But in the background, it’s pushing malware to your smartphone, and now, just like that, the threat actor behind the scenes can monitor everything you do on that device.

This is typosquatting. It’s been around for decades. But in 2026, it’s arguably more stealthy, malicious, and widespread than ever.

This guide explains how typosquatting works, how it is evolving, and what individuals, security teams, and brand owners can do to defend against it.

What is typosquatting?

Typosquatting (aka URL hijacking, or look-alike domain attack) occurs when threat actors register domain names that are intentional misspellings or close variations of legitimate sites. The goal is to capture users who mistype URLs or click on look-alike links - usually to steal their information, install malware, or otherwise generate illicit revenue.

Typosquatting is a form of cybersquatting, where bad-faith individuals register domains that are identical or similar to existing trademarks in order to profit from them.

Why it’s so successful

Typosquatting continues to reap rewards for cybercriminals because humans are imperfect creatures. We often prioritize speed over accuracy when typing, especially on our devices, and fail to double check URLs before we click.

More than a nuisance: parked domains and redirect farms

There was a time when typosquatting domains were simply parked (e.g. registered without being actively used) and showed generic ads. That is no longer the case.

Research reveals that over 90% of the time, visitors to parked domains are directed to illicit content, scams, scareware or malware. In some cases, users are profiled and routed to different malicious pages depending on device, location, or previous web traffic.

The bottom line is this: typosquatting is no longer a minor nuisance. It could be a significant security risk to both individuals and organizations.

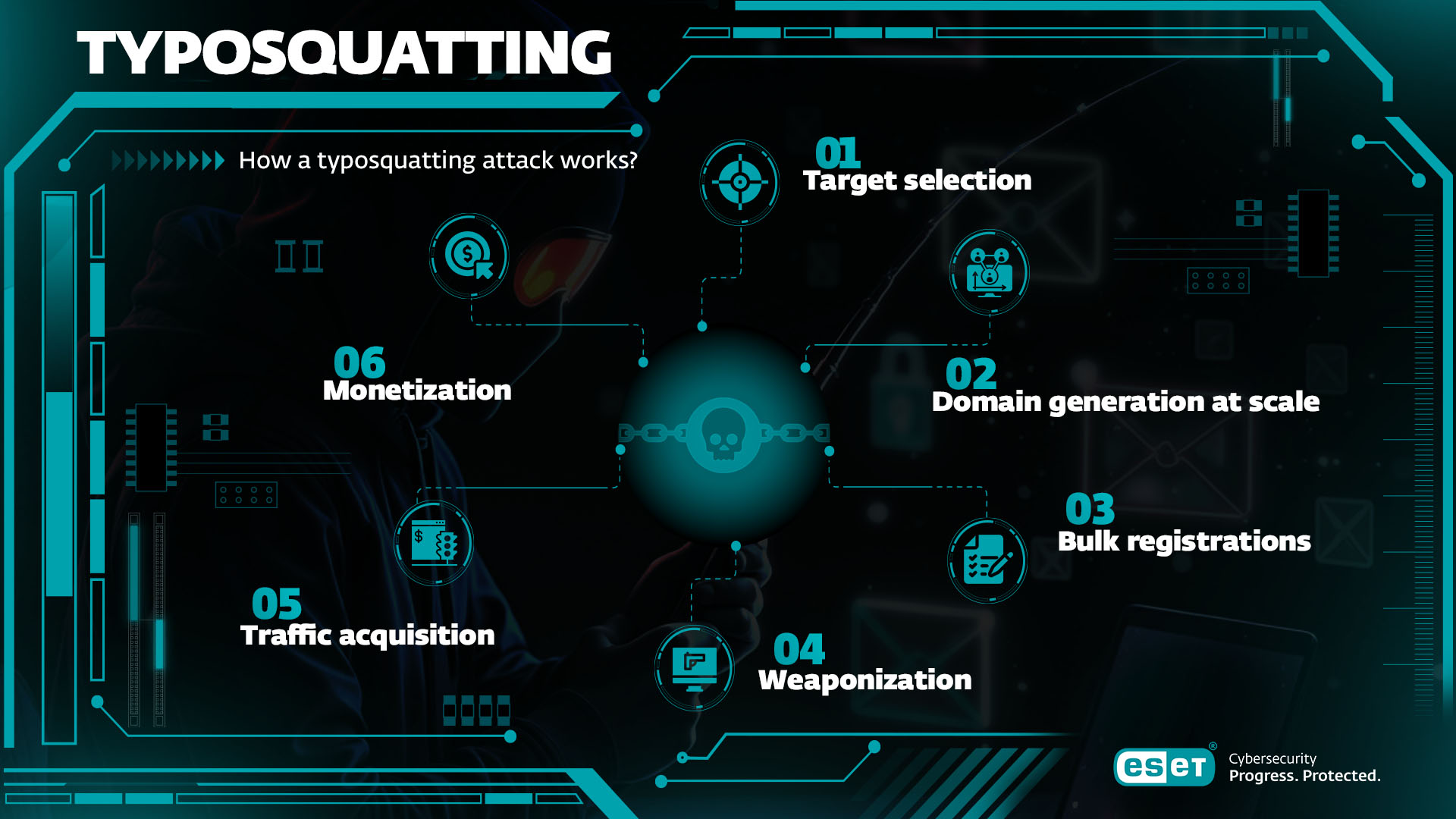

How a typosquatting attack works

Today’s typosquatting campaigns are not one-off projects. They are highly automated, data-driven cybercrime operations. Here’s what happens:

Typical attack chain:

- Target selection: Attackers perform reconnaissance, usually selecting high-value domains belonging to banks, technology providers, e-commerce firms, crypto exchanges, and other big-name businesses.

- Domain generation at scale: They use automated tools like dnstwist to generate thousands of variants (see next section).

- Bulk registrations: Attackers register these variants in batches, using low-cost domain registrars or resellers, often using stolen credit cards. By registering large volumes of domains at a time, they stand a better chance of tricking automated detection systems.

- Weaponization: The threat actor links the domains to infrastructure including lookalike phishing pages, malware payloads, and scam ad networks. If registering a phishing page, they may use HTTPS to build false trust.

- Traffic acquisition: Cybercriminals don’t just wait for victims to arrive via manual typos. They might also proactively lure them via phishing/smishing links, QR codes, and malicious ads (malvertising).

- Monetization: They will try to turn those typosquatting domains into revenue as quickly as possible before they are blacklisted. This means monetizing stolen credentials and malware infections or making money through affiliate fraud and scam funnels.

The seven main types of typosquatting

Typosquatting can be classified into seven primary patterns. All of them show up regularly in real investigations and incident reports:

- Fat-finger misspelling: To attract users that hit an adjacent key or duplicate a character. Eg, “examplw.com” instead of “example.com”.

- Omission: A character, often one of the double consonants, is missing. Eg, “dropox.com” instead of “dropbox.com”.

- Transposition: Two adjacent characters are swapped; a very common fast-typing error. Eg, “micorsoft.com” instead of “microsoft.com”.

- Top-Level domain (TLD) swap and country code TLD abuse: Attackers register the same or very similar name on a different TLD, often one visually close to the original TLD. Eg “amazon.co” instead of “amazon.com”.

- Combo-squatting: Instead of misspelling the brand, attackers add legitimate-looking words to the beginning or end of the domain. Eg, “coinbase-support.com” instead of “coinbase.com”. This is a popular tactic for links in phishing emails as it helps bypass filters only looking for simple misspellings.

- Missing dot: The dot between subdomain and main domain is removed, often turning what looks like an internal host into a single deceptive domain. Eg, “financeyahoo.com” instead of “finance.yahoo.com”.

- Homograph attacks: Homograph or IDN attacks replace commonly used ASCII characters with visually similar letters from other alphabets (e.g. Cyrillic), then encode the domain with Punycode. E.g., “аррlе.com” might use a Cyrillic “a”.

Advanced variants

Beyond the seven basics, two newer trends are starting to emerge:

Package and dependency typosquatting

Malicious open source packages are uploaded to registries like PyPI and npm, using names that differ by a single character from popular libraries, in order to trick developers into downloading them.

Blockchain naming and crypto-handle squatting

In blockchain naming systems such as Ethereum Name Service, attackers register lookalike identities and domains to misdirect cryptocurrency transactions or impersonate popular projects.

Typosquatting in the mobile, AI and crypto era

Why mobile users are easier to trick

Typosquatting success rates are higher on mobile for a few simple reasons:

- Touchscreens increase the chances of typos

- Smaller screens make it more difficult to check URLs

- Browser address bars hide most of the URL

- Long domains are truncated to show only the beginning

- Users rely more heavily on autocomplete and search suggestions

- Users are more likely to react to ‘urgent’ phishing messages directing them to click

- There is no hover function which, on a desktop, allows users to check a full URL before they click through

AI-assisted domain generation

Cybercriminals are increasingly experimenting with AI to enhance typosquatting and increase success rates. It can be used to:

- Generate brand-consistent typosquatting (e.g. combo-squatting variants) at scale

- Identify typosquatting domains that will evade brand monitoring

- Build effective lookalike phishing pages in flawless language at scale

- Achieve “slopsquatting” attacks, by anticipating hallucinated software libraries/packages, which can then be pre-registered

Crypto and “address poisoning”

In crypto ecosystems, typosquatting has morphed into address poisoning. Attackers create wallet addresses whose first and last characters match the address of a victim or someone they trust. They then send the victim a tiny amount of crypto or zero-value token transfer from this copycat address, which is then automatically listed in recent activity.

The next time the victim wants to move funds, they might copy what they think is a trusted address (because these tend to be truncated in the wallet’s user interface). In reality, it is the look-alike scam address.

Typosquatting vs cybersquatting

Cybersquatting is a form of domain abuse where attackers register domains using names of popular legitimate brands or resembling them. This practice often involves typosquatting. Although the concepts are related, they’re not identical:

Aspect Typosquatting Cybersquatting Domain pattern Typo, near-look-alike, alternative TLD Exact or very close match to a trademark or personal name Primary goal Phishing, malware, ad fraud, credential theft Resale, extortion, traffic hijack, reputational leverage Legal focus Often handled under fraud, phishing, and sometimes Anti-cybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) when confusing similarity is shown Directly addressed by the ACPA and Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP) processes

In practice, many typosquatting disputes are treated as a subset of cybersquatting when they involve confusing similarity to a protected mark and bad-faith intent.

Risks for individuals and organizations

Typosquatting can have serious consequences, not only for home internet users but also for organizations. Here’s how:

For individuals it could lead to:

Phishing pages designed to harvest personal information, as well as credentials (e.g. usernames and passwords) for sensitive sites like email, cloud storage, and social networks. Personal info can subsequently be used for identity fraud.

Malware such as spyware and ransomware, distributed via drive-by-downloads.

Financial loss via fake banking/payment, crypto and e-commerce sites which harvest your card and banking information.

For businesses it could lead to:

Brand damage and loss of trust if customers are taken to a fake domain and end up blaming the real company rather than the copycat scammers.

Data breaches and ransomware could stem from a typosquatting domain placed within a phishing email targeting an employee. Alternatively, staff may mistype the URLs of internal portals or SaaS admin panels.

Business email compromise (BEC) attacks often feature a typosquatted email domain - either spoofing the CEO or perhaps a supplier.

Traffic and revenue loss, as customers are redirected to competitors, affiliate fraud schemes, and malicious sites.

Legal and operational cost related to pursuing Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy (UDRP) cases or litigation, and handling customer support, incident response, and PR following impersonation events. This is time and budget which could have been used elsewhere.

Detection: how security teams can spot typosquatting

Effective defense starts with visibility. Mature security operations center (SOC) and threat intelligence teams typically combine several techniques:

Fuzzy matching and similarity scoring

Algorithms such as Damerau–Levenshtein (for transposition) and Jaro-Winkler (for combo-squatting) provide multi-layered detection capabilities, calculating the similarity between visited domains and the legitimate ones.

Certificate Transparency (CT) monitoring

Most HTTPS sites obtain publicly logged Transport Layer Security (TLS) certificates, i.e. digital authentication credentials for websites. Monitoring CT logs for look-alike names is now standard practice among domain security and DMARC vendors.

Domain Name System (DNS) telemetry and passive DNS

These provide early warning indicators including:

- Sudden spikes in NXDOMAIN (Non-Existent Domain) queries around a brand keyword

- Newly active domains under rare TLDs that resemble protected names

- Overlaps in hosting infrastructure or name servers with known malicious campaigns

Threat intelligence feeds

Security researchers share feeds of known typosquatted domains, lookalike certs, and associated phishing kits, which can then be integrated into web proxies, secure email gateways, and SIEM correlation rules.

Brand and marketplace monitoring

Proactively watch for new domain registrations that contain trademark strings or known combo-squatting patterns. Enterprise demand for this type of protection continues to grow as brand impersonation cases increase.

Prevention for general users, IT teams and legal departments

Detection is one thing, but prevention is always the preferred option if possible. Consider the following:

General users should:

- Use bookmarks for often used sites (e.g. banking, email) rather than typing in URLs each time

- Use apps for frequently used services, rather than the website equivalent

- Use search for discovery, as most reputable providers apply typo correction and have strong phishing detection

- Look beyond the padlock symbol in the URL, as HTTPS only means that connections are encrypted, not that the site is trustworthy

- Install and maintain security software from a reputable provider. It should include web protection and anti-phishing features that check domains against global threat intelligence, and block connections to known malicious destinations

- Use a password manager, because they are designed not to auto-fill credentials on the wrong domains

- Avoid clicking on links in unsolicited emails, text, chat, and social media messages, or on unknown websites.

IT, security, and SOC teams should:

- Harden their domain footprint by registering the main variants and most obvious typos for primary domains, as well as defensively registering across alternative TLDs

- Deploy modern email and domain security to enforce SPF, DKIM, and DMARC email authentication protocols on outbound domains, and implement inbound DMARC checks and lookalike sender domain controls

- Use DNS filtering and secure web gateways to block known malicious and new domains at the DNS layer

- Monitor CT logs and domain registrations, and set up alerts for certs and registrations that feature the corporate brand name

- Train employees with real-world examples and simulation exercises

Brand, legal, and executive teams should:

- Define a brand protection policy by identifying which domains/TLDs to defensively register and set a threshold for escalating to legal action/UDRP

- Coordinate with marketing and security teams to vet campaign domains, sites, and QR codes for look-alikes, and avoid confusion

- Plan for response as well as prevention by keeping templates for registrar abuse reports and takedown notices, and preparing customer communication plans for when impersonation happens

Expert tip & insights

“Typosquatting remains one of those threats that exploits the most human elements of cybersecurity, as our fingers can often move faster than our brains. What makes this particularly subtle is that the domains they lead to can even look identical once you land on them, especially now that AI is making it easier to clone websites.

The scary part is that it’s not just about stealing passwords or data anymore. Modern typosquatting techniques can now deliver malware or even collect session tokens. And because these domains are actually legal to register until they are proven malicious, they can sit there for months before they are taken down.

To stay safe, it is best to steer away from typing in web addresses. A straightforward way to avoid these risks would be to use a password manager with autofill because it won’t make typos.”

- Jake Moore, Global Security Advisor

Stay safe from typosquatting – protect your entire digital life

Typosquatting is just one of many online threats. ESET HOME Security Premium delivers complete protection for your digital life, including advanced web and anti-phishing security, identity and privacy safeguards, and multi-device coverage. Stay secure wherever you browse, shop, or bank.

Key Takeaways

Typosquatting now plays a key role in cyber and fraud campaigns, as an enabler for malware delivery, phishing, BEC and more.

Use of AI and automation enables cybercriminals to scale typosquatting and make it more effective, while the mobile device user experience makes attacks harder for victims to spot.

There are multiple techniques for typosquatting, ranging from domains with a missing or swapped letter, on to those with extra words added on to them and even the use of different alphabets.

The threat is evolving and now even presents a real danger to open-source software developers and cryptocurrency users.

Effective defense is layered and role based. Users should rely on bookmarks, apps, password managers, and security software. IT teams should use DNS filtering, CT monitoring, and threat intelligence. And brand/legal teams should pursue defensive registrations and enforcement.

Human error is inevitable. But compromise via typosquatting is not. By taking extra precautions and enhancing detection, prevention and legal enforcement, users can take the fight to adversaries.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is typosquatting illegal?

Typosquatting that involves confusingly similar domains used in bad faith (e.g. to impersonate a brand or steal credentials) is often actionable under trademark law and the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (ACPA) in the US. Whether a particular case is illegal depends on jurisdiction, the exact domain used, and the attacker’s intent, so legal counsel should be consulted.

Why is typosquatting so successful?

Because humans often prioritize speed over accuracy when typing, especially on their devices, and fail to double check URLs before they click.

What could typosquatting lead to?

Threats include phishing and credential theft, identity fraud, financial loss, and malware infection.

How do I report a typosquatting site?

You can report it to your security or browser vendor, contact the domain’s registrar or hosting provider, or consult your legal team to evaluate UDRP/ACPA options.

Can a VPN protect me from typosquatting?

A VPN protects the confidentiality of your traffic and may help on untrusted networks, but it does not prevent you from visiting a malicious lookalike domain. You need DNS filtering, browser protection, and anti-phishing capabilities for that.

What is the difference between phishing and typosquatting?

Typosquatting describes how users are lured to the attacker’s infrastructure through look-alike domains or URLs. Phishing is what happens once they arrive: the attempt to trick users into revealing data or performing harmful actions. The two are often combined, but not all phishing uses typosquatting, and not all typosquatting sites host phishing content.

What’s the difference between typosquatting and cybersquatting?

Typosquatting is a type of cybersquatting. The latter relates to the registration of an exact or close match to a trademark or personal name in order to profit from it. Typosquatting involves misspellings in website addresses and is usually linked to phishing, fraud, and malware delivery.

Can companies fully prevent typosquatting?

No brand can completely stop others from registering similar names. But by combining defensive registrations, monitoring, DNS and email security, and legal enforcement, you can significantly reduce risk and impact.